September is pain awareness month, aimed at raising public awareness, empathy and understanding of pain, particularly chronic, to advocate for advancements in pain management. While pain in humans is usually categorized on a subjective scale by asking the patient how bad the pain is at any given moment, horses are, obviously, unable to do so. However, assessing and treating pain remain critical for equine welfare.

As prey animals, horses will often try to mask pain and disability to avoid predation. This makes it even harder to assess pain levels in some horses. Although there is said to be some difference in pain tolerance levels between some breeds, with native and heavier horses and ponies often thought to be more resistant to pain than warmbloods or thoroughbreds, this is not always the case. Temperament and perception of threatening situations seemingly more likely to affect how, and to what level, horses display symptoms of pain.

Pain Scales

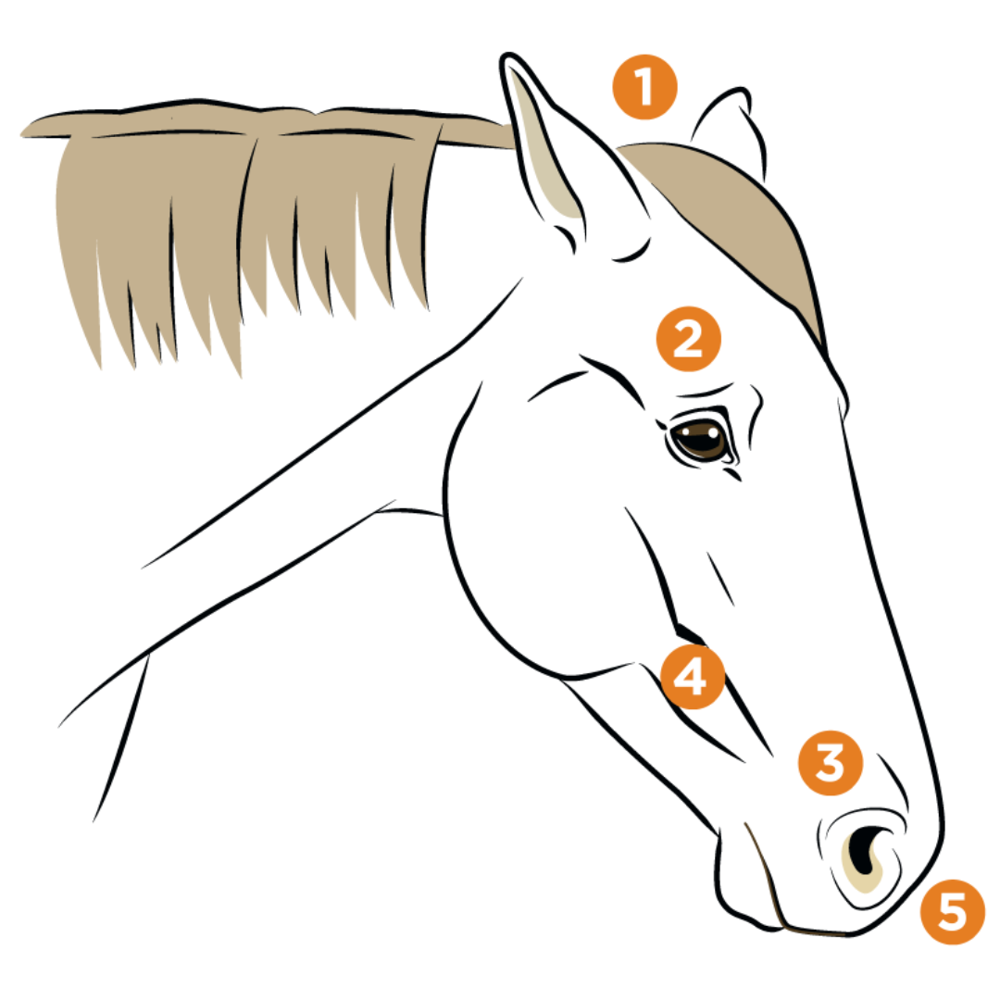

Over the years various scales for assessing pain levels in horses have been developed, with the Horse Grimace Pain Scale being one of the more frequently used. This assesses and scores facial expressions including:

- Ear position.

- Orbital tightening, with eyelids partially closed.

- Tension above the eye area.

- Strained chewing muscles; increased tension above the mouth.

- Strained mouth with upper lip drawn back and lower lip causing a pronounced chin.

- Strained and slightly dilated nostrils, with a flattened nose profile.

However, as horses are all individuals and show pain in different ways, only looking at facial expressions may not provide a full picture. More comprehensive models that look at a composite pain score (CPS), which is a combination of different interactive, psychological and physiological parameters associated with pain, seem to be more reliable indicators. Studies evaluating these types of pain scores tend to show good inter-observer reliability, meaning that if several people look at the horse independently, they all come to the same pain score. This is important in any setting where the horse is looked after by more than one person, or in settings where the owner isn’t always the primary person in contact with the horse such as in a livery yard or veterinary hospital.

One such CPS scale developed in 2019 uses individual scores of pain face, activity levels, location in stable, posture (including head position), attention to the painful area, interaction with people and surroundings, response to food, breathing rate and heart rate to create an overall score, assessed over a period of 10 minutes. This method showed good inter-person reliability, making it suitable for use in a variety of settings.

Being able to reliably identify pain is not only an immediate welfare issue, but addressing it quickly it can also prevent manifestation of further issues. Chronic pain, even low grade, can increase circulating levels of the stress hormone cortisol. This has wider effects on physiology including suppressing the immune system and weakening the mucosal layer that covers the stomach lining. Without an effective mucosal layer the stomach acids are more likely to reach the delicate epithelial cells and cause ulcers, particularly in the lower glandular region.

With all the different ways of assessing pain it is apparent that experiences of pain are highly individual. No two horses will express pain in exactly the same way, or the same level of response to an identical stimulus. Pain may be expressed as a wide variety of different behavioural changes, facial expressions, increased fussiness around food or differences in how they interact with other horses and people. With all of this in mind, it’s vitally important that we get to know our horses both from the ground and under saddle, spending time with them, and paying attention to all of their little details and quirks. In so doing, we’ll be much better at picking up on the signs of anything untoward and able to provide appropriate pain management and care as quickly as possible.