It can be a nerve-racking time when breeding horses, with many management and nutritional factors to consider along the way. Factors generic to all broodmares and their foals need to be considered in the context of the individual animal’s requirements to allow appropriate decisions to be made that support the health and welfare needs of the mare and her foal.

Understanding the mare's gestation period:

How long is a mare's gestation period?

The gestation period averages 340 days (11 months) but can vary between 320 and 380 days. Gestation length and, therefore, the foaling date is influenced by environmental, foetal, and, most importantly, maternal factors.

Factors Affecting a Mare's Gestation Length

Environmental factors influencing gestation length include seasonal conditions or climate, the amount of sunlight the mare receives each day (also known as photoperiod), and when the mare was mated within the season. Many studies have found that gestation length was significantly reduced when mares were mated at the end of the season (July to November) compared to at the start (January and February). Foetal factors include genetics, the sex of the foetus, and the type of pregnancy, with research showing that male foetuses tend to lead to slightly longer pregnancies, whilst in the case of twins if the pregnancy is successful, the gestation period tends to be much shorter. Maternal factors such as nutritional state, age, breed, and number of births the broodmare has had, if any, will effect gestation length. Older mares may have decreased nutritional efficiency of their uterus and placenta, meaning that gestation length is increased as the growth process becomes slower, and mares who receive optimal nutrition, rather than just a maintenance diet, have been seen to have shorter gestation lengths.

Understanding the due date of the foal

What the foal is being bred for is likely to determine the month that it is due. For example, a foal that is expected to have a racing career is likely to be due earlier in the foaling season than a sport or leisure horse, as those with racing careers begin training much sooner and so will be more developed if they are born earlier. Some more commercial broodmares may have a foal every year, making the first month after having the previous foal incredibly crucial to set her up within a short time period for her next pregnancy.

Studies have shown that day length can affect foaling dates with longer gestation lengths decreasing the possibility of mares coming back into oestrus within the same covering season. Although many breeders will know the due date of the foal, a vet can help determine this more accurately using blood tests and scans, to ensure you are ready for the birth, as all of these factors must be considered when predicting the date that the mare is due to foal and begin lactating.

Changing the Mare's Nutritional Needs During Pregnancy

Feeding requirements are not only different as the pregnancy and lactation period progresses but are also dependent on the time of year and weather conditions as the nutritional quality of grazing will vary and poor weather increases the mare’s energy requirements. The mare can start lactating early, up to a month before foaling, or wait until only a few hours before giving birth before she produces any milk.

Lactation will continue until the foal is weaned or until approximately 6 months after giving birth. Lactation is a critical period in the mare's breeding cycle as it is the most nutritionally demanding period for the mare as she provides nutrients to the growing foal. Milk yields can range from 2 to 3% of the mare’s body weight per day, so for a 500kg mare this equates to her producing 10-15 litres of milk daily. Such demands make it easy to understand why her nutritional needs are at maximum during the lactation period. Providing a diet that meets the mare’s nutrient and energy requirements will allow her to adequately nurse her foal whilst remaining healthy herself.

Recognising Signs of Foaling and Labor in Mares

Whilst foaling may be unexpected, many signs are clear and round the clock observations can ensure help can be provided quickly if any problems occur. Many births occur during the evenings and early morning, although there is always the chance of a daytime birth. Monitor the mare’s mammary gland for when she begins bagging up (Figure 1), which usually occurs two to three weeks before foaling whilst waxing often appears in the last few days of pregnancy. Behavioural signs such as the mare seeming unsettled, restless, or stressed, and abnormal movements can indicate labour has begun. Defecating and urinating little and often, and not wanting to eat as much as normal are further signs of imminent labour, however these signs are similar to those exhibited by horses with colic, meaning it can be difficult to differentiate between signs of labour and those of colic. Colic is common amongst heavily pregnant and newly birthed mares, therefore close monitoring of the mare is needed.

Figure 1. Mare with an enlarged udder, also known as ‘bagging up’, due to the production of milk in preparation for the birth of the foal

Considerations during foaling:

Ensuring Comfort and Managing the Mare's Diet During Foaling

Making the mare as comfortable as possible is key, so by keeping the mare in a regular routine and keeping her calm leading up to, during, and immediately after the birth will aid the chances of the mare’s survival and a safer delivery of her foal. Maintaining her routine includes what she is fed as sudden dietary changes can increase the risk of colic. Providing a feed that can be gradually increased in quantity when needed, rather than completely changing the feed type or brand, is preferable. The diet should be palatable to encourage eating and optimise intake and based on an ample supply of suitable forage.

Nutritional Changes During Pregnancy for Optimal Foal Growth

The nutritional needs of the mare change throughout her gestation period as placental growth takes place during early pregnancy and the final three to four months is when the majority of foetal growth takes place. From the fifth month of gestation onwards the mare’s energy and crude protein requirements increase, therefore an increase in dry matter intake (DMI) is likely needed.

Research has found that providing excess energy in late gestation did increase the mare's body weight and condition but did not increase the foal's birth weight, however horses that have their late gestation period in the winter months may have increased energy requirements due to more energy being needed to maintain body temperature.

Ideally, the pregnant mare’s diet will contain 16% crude protein (CP), with a good supply of Lysine, the first limiting amino acid making it an essential amino acid. The Lysine requirement can be calculated by multiplying the CP requirement by 4.3%, therefore high-quality protein must be provided in the diet. Cereal grains are often low in essential amino acids and therefore provide low-quality forms of protein, whereas high-quality protein can be found in feedstuffs such as Soya bean meal, Brewer’s Yeast and Alfalfa.

Key Vitamins and Minerals for Pregnant Mares

Vitamin A and E requirements are higher than that for maintenance throughout pregnancy whilst Calcium and Phosphorus needs increase a small amount in months 7-8 and larger amounts in months 9-11. Copper and Iodine requirements also increase in months 9-11 but there are no increased needs for Iron, Manganese, Zinc or Selenium.

From this information it is easy to see why increasing a general vitamin and mineral supplement could meet the increased requirements of certain nutrients, but oversupply other nutrients. Feed or supplements specifically designed for breeding animals is advised to ensure requirements are met in the correct balance.

The Role of Prebiotics, Probiotics, and Pasture Access

The addition of prebiotics and probiotics can be helpful in supporting the normal function of the mare’s gastrointestinal tract, although these should be incorporated into her normal diet prior to the physically demanding labour. Turning the mare and the new-born foal out to pasture as soon as possible helps to keep the mare moving and grazing, and may also reduce the risk of colic.

Nutritional Management During Lactation:

Pasture Quality and Supplementation for Lactating Mares

Pasture is the most desirable source of forage for the lactating mare as it provides a better source of energy, protein, vitamins and minerals compared to preserved forages such as hay. Despite being such a good food source, pasture may not necessarily provide all nutrients the mare requires as its nutrient content depends on various factors such as the grass species, soil type, climate, and time of year that the mare is grazing. Analysing soil and grass can be helpful but can prove expensive and might not always be accurate. Providing a feed or supplement specifically designed for breeding mares is advised to ensure all nutrient demands are met. Mares that are to be stabled more frequently will also require additional vitamins and minerals through a concentrate feed or supplement. The better the quality of forage the mare receives, the lower the amount of concentrated feed she will need to be fed, however not all vitamin and mineral requirements may be met if feeding less than the recommended daily amount of feed, meaning supplementation is likely to be needed. If mares are kept as a group at pasture, it may be difficult to feed individually and ensure they are receiving the desired nutrients, so feeding in individual stables or pens can ensure the correct amounts are received.

Increased Nutritional Demands and Milk Production During Lactation

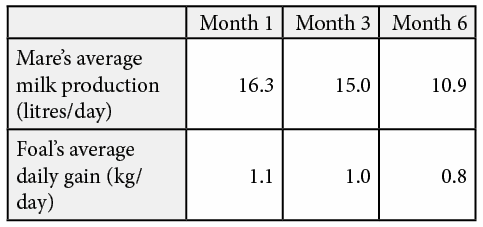

The lactation period brings about the most sudden changes in nutrient requirements and this is when the broodmare’s nutritional needs increase the most. Providing the mare with optimum nutrition will enable her to produce enough high-quality milk for her foal. In the first month of lactation a 500kg mare will produce an estimated 16.3 litres per day of milk (Table 1), with this amount reaching maximum when the foal reaches about 6 weeks of age. After this period the amount of milk gradually reduces, coinciding with a slowing of the foal’s rate of growth (average daily gain in body weight measured in kg). By the sixth month of lactation the same mare would be producing only 10.9 litres of milk per day.

Table 1. Average milk production (litres/day) for a 500kg mare during months 1, 3 and 6 of lactation, and the average growth rate of a foal at months 1, 3, and 6 of age

The nutritional needs of the mare vary in response to her maintenance requirements and stage of lactation, with early lactation classed as up to 12 weeks and late lactation being from 12 weeks onwards. Maintenance requirements are the amount of nutrients the mare requires to maintain her own body and normal functions, which increase by approximately 10% in lactating mares. Mares managed outside will have higher maintenance requirements as they generally spend more time moving and also have to regulate their own temperature in different weather conditions. In addition to maintenance requirements, the mare also requires specific nutrients for milk production, with the higher milk production in early lactation requiring higher nutrient intakes compared to requirements during late lactation when milk production is less.

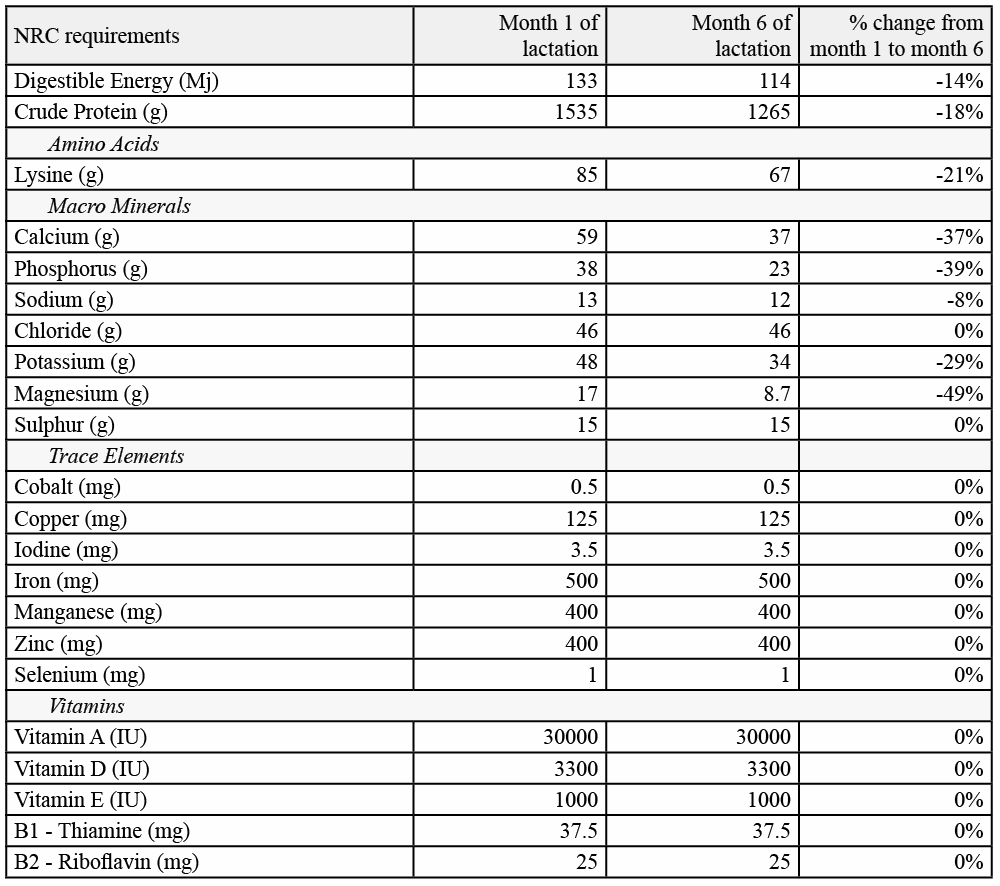

Table 2. Daily nutrient requirements of a 500kg broodmare in the first and sixth month of lactation

Calculations based on NRC (2007) recommendations

Table 2 shows the nutrient requirements of a 500kg mare in her first and sixth month of lactation, respectively.

Energy Requirements for Lactating Mares

The energy requirements of the lactating mare are almost double that of a mare at maintenance or in the early stages of pregnancy. As energy demand is associated with the amount of work the body has to do to produce milk, the highest energy demands for the mare are during early lactation due to her having to produce large volumes of milk for her rapidly growing foal.

Table 2 shows how the energy demand at six months lactation is reduced, although it still remains considerably higher than the energy requirement of even mares at the end of their pregnancy. The mare is able to convert about 60% of her digestible energy into milk energy and providing a diet of good quality forage can reduce the need for concentrates to be fed to meet energy requirements.

Sufficient good quality grazing and hay are likely to be able to meet the broodmare’s energy needs, however all horses will greatly vary so must be reviewed individually, with assessment of their fat stores the easiest way of determining if your mare requires more or less energy, as energy consumed in excess of requirements will be stored as fat. It is possible that feeding a mare on a forage only diet throughout her gestation, whilst meeting her energy requirements, could reduce the risk of her foal developing osteochondrosis by eight times compared to those fed concentrates during gestation. It should also be noted that providing the mare with excess energy will not increase the growth rate of the foal and may even produce higher quantities of less concentrated milk.

_1000.png)

Figure 2. A balanced diet is essential for the mare to ensure her milk can provide the nutrients the foal needs for correct growth and development

If the mare’s diet is severely deficient in energy, especially if she has a low body condition score prior to foaling, then she will likely lose weight and this can reduce foal birth weight and growth). If only in moderate energy deficit (80% of energy requirements met) it is unlikely to have any effect of foetus growth or the foal’s growth after birth due the placental adaptation.

Protein Quality and Amino Acid Balance for Milk Production

Protein requirements for a mare in early lactation are triple those of the mare when she is not pregnant. This considerable increase in protein requirements shows how simply feeding more feed is unlikely to meet nutritional demands of lactation, as the mare would need to consume large amounts of feed to satisfy protein demands which would likely result in too much energy being consumed and an increase in fat stores. The mare’s requirements for protein are greatly increased due the vast amount of protein passing from her to the milk. Mares are able to convert approximately 35-40% of their crude protein intake into milk protein, depending on the protein quality, and so a good balance of amino acids and highly digestible protein should be provided. Insufficient protein in the diet over a prolonged time will decrease milk production and cause the mare to lose muscle and topline, whilst a diet containing protein comprising non-essential amino acids (known as low quality protein) results in a reduced milk yield.

We can see from Table 2 that in the early stages of lactation, a 500kg mare requires 85g of the essential amino acid Lysine and so over 5% of her crude protein intake must contain Lysine. Due to the requirement for essential amino acids in the body, it is more important to meet the amino acid requirements of the mare than the overall crude protein needs. Achieving this may mean that the amount of protein in the diet is increased to meet the amino acid demand.

Essential Vitamins and Minerals for Lactating Mares:

Whilst some vitamins and minerals may have a greater influence than others, it is not only the quantities that they are supplied in the diet that must be considered. Some nutrients should be fed in the diet in specific ratios to aid correct utilisation and avoid them competing for absorption or influencing the uptake of other nutrients, especially when some are provided in excess.

The mare will also have an increased need for water with studies showing that broodmares require 1.8 to 2.5 times more water than is needed for a horse at maintenance. Keep clean fresh water available at all times, ensuring troughs do not freeze if outside. Monitoring the mare's water intake just prior and during labour can indicate potential problems.

Calcium and Phosphorus

The Calcium to Phosphorus ratio in the horse’s skeleton is 2:1, and 1.7:1 within the whole body. Calcium is the mineral that creates a strong skeletal system and therefore the lactating mare has an increased demand to ensure that her suckling foal receives sufficient quantities for its skeleton to grow and develop. Calcium requirements for lactating mares are 1.8 to 2.8 times higher than a horse at maintenance, with the highest levels during the early stages of lactation (months 1 to 3).

Providing insufficient Calcium increases the chances of bone demineralisation, yet over-supplementing does not provide any additional benefit to the foal’s skeletal development. It is also shows that Phosphorus requirements increase by similar amounts (1.7 to 2.7 times maintenance requirements), with the highest levels during early lactation.

Iodine, Selenium, and Vitamin E Requirements

Iodine is highly digestible and is vital for the synthesis of thyroid hormones such as thyroxine and triiodothyronine, which are needed to regulate the horse’s basal metabolic rate (energy expenditure at rest). Selenium also aids thyroid hormone metabolism as well as acting as an antioxidant. The trace nutrients Iodine and Selenium play an important role and should be balanced in the diet as these trace elements can affect the mare’s fertility and viability of her foal, whether the mare's diet is providing excess or deficient amounts.

Vitamin E a well-known antioxidant crucial to support the horse’s immune system and can often be seen paired in supplements with Selenium. Whilst toxicity of Vitamin E is unlikely, inadequate intake of Vitamin E and Selenium during the mare’s pregnancy and lactation period has a direct effect, causing deficiency in her foal from birth to one month of age. Research has found that supplementing mares with Vitamin E during the late gestation period resulted in higher levels of immunoglobulins in their milk and their foals were found to have improved immunoglobulin levels and Vitamin E status.

Monitoring Body Condition and Fat Stores:

Monitoring the fat stores of the mare is a simple yet effective way of adjusting the amount of energy being consumed as it allows the breeder to visually monitor the mare with little stress or change in routine. Maintaining optimum fat stores is key throughout the pregnancy and crucial during lactation as some mares prone to weight gain, such as heavy breeds or ponies, will require close monitoring and an appropriate feeding regime to reduce excess fat accumulating. Excess body weight also increases strain on the musculoskeletal system which can impair her mobility and comfort.

If energy requirements are not met, the mare will use her own body fat stores to continue lactating, resulting in weight and condition loss. A suckling foal can rapidly lower the fat stores of an already thin mare. Once a lactating mare has lost condition it can be difficult to regain as an increased amount of feeding, especially large volumes of concentrates, could lead to other risks such as colic. This emphasises the importance of the mare being in optimal condition before foaling. A mare with excessive weight and a mare that is underweight can both cause issues during foaling and there can be ongoing implications for the mare’s health.

Summary:

Caring for the broodmare can seem daunting as there are many factors to consider, however it should be remembered that the mare can be fed and managed as normal until the 5th month of pregnancy, when the requirements of energy and some nutrients increase. After this time it is recommended to review her diet and management to optimise foetal development and mare health, and to keep these under review throughout the remaining pregnancy and during lactation, making any changes gradually. For many mares, a forage-based diet supplemented with vitamins, minerals and quality protein will meet all of their requirements whilst avoiding the likelihood of excess weight gain.

If you would like any advice, please contact our Equine Nutrition Team who would be happy to help. You can email [email protected] or call our freephone advice line on 0800 585525.