Introduction

In this article, we will review the nutritional requirements of growing foals. For the first six months of the foal’s life, its diet predominantly consists of the mare’s milk, with small amounts of grass, forage, and concentrate feeds also being consumed. As the foal nears the time to be weaned from its dam the proportion of milk in the diet reduces whilst the amount of other foods increases, meaning there needs to be consideration of what feedstuff to offer and how best to allow the foal to develop into a strong yearling, regardless of what their future lifestyle maybe.

Figure 1. Weaning can be a stressful time for both foal and mare. Where possible wean foals in pairs or small groups to allow them to develop bonds with others which helps to reduce stress.

Understanding Weaning and Its Impact on Foals

A weanling is a horse that no longer relies on and suckles on their mother’s milk. Weaning usually occurs when the foal is between four and six months old, although when the foal is weaned will depend on a number of factors that could be related to the foal or its dam. If the foal is growing too fast, gaining too much body fat, or showing any signs of developmental orthopaedic diseases (DOD) or other conformation defects, then weaning may take place sooner so the nutrients the foal receives can be controlled. Weaning may also take place early if the dam is unable to supply enough quality milk or if she is losing condition. Weaning can be an incredibly stressful time for both mare and foal as ultimately the mare and foal are separated, and the is foal mixed with a group of young horses (Figure 1). Creep-feeding your weanling is a good idea to gradually introduce them to hard feed if the dam has not been receiving any, as this will help to reduce stress at weaning time and ensure they begin receiving a balanced ration.

The Importance of a Balanced Diet for Weanlings

As most weaning takes place when the foal is six months old, we will explore the foal’s nutritional requirements starting from six months of age. A balanced, nutritional ration is extremely important for the weanling as they are at a vital stage of growth, and how well they are able to grow at this stage will influence their future athletic potential, with insufficient nutrients having the potential to cause health problems later in life. A weanling will eat less than a yearling in volume but still requires certain nutrients so a nutrient-concentrated diet is ideal.

Energy Requirements for Growing Foals

The energy requirements of the weanling are partitioned into energy for maintenance (normal body functions and activity) and energy for growth. As growth rate is greatest at this age the weanling requires considerable energy for its body size. This is evident by comparing the daily 70Mj of digestible energy (DE) required by a 500kg horse at maintenance, to the 65Mj DE required by a 6-month-old weanling weighing an estimated 216kg.

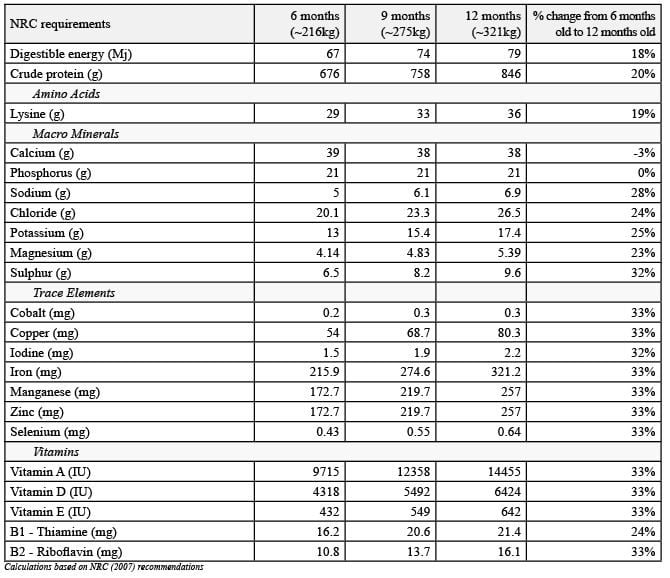

As shown in Table 1, the DE requirements of the foal increase as it gets older due to the increase in body mass. The estimated daily weight gain at six months old is 0.72kg per day, at nine months old it is 0.57kg per day, and at twelve months old it is 0.45kg per day. This shows that although growth rate slows down over the months, the weanling still requires increased energy for maintenance and development due to their increased body size. As youngsters mature and development slows down, the amount of energy required for development reduces, aligning their overall energy requirement to that of adult horses once they mature.

Factors affecting the weanling's energy requirements:

The weanling’s energy requirements will also vary depending on their date of birth, climate, condition, and individual metabolism. Foals born in early spring tend to have a heavier birth weight than those born later in the foaling season. As all foals tend to be weaned at similar times, those born earlier are older at weaning and so generally have greater energy requirements. Colder conditions will increase the energy demand of the weanling, however, this may decrease over time as they acclimatise to the low temperatures. Whilst some breeds are considered easy keepers, such as drafts and native pony types, others such as Thoroughbreds are classed as hard keepers and therefore can have slightly higher energy requirements which should be factored into their feeding rations. Whilst the foal is still suckling, the mare’s milk will provide almost all of the required energy, and as the foal gets older forage will become an increasing part of their diet, and concentrate feed may also be introduced to the weanling. Weanlings who are energy deficient will have a reduced growth rate and reduce their chances of reaching their potential.

Table 1. Daily nutrient requirements for the weanling at six, nine and 12 months old with a predicted mature weight of 500kg.

Take care to not exceed the weanling's energy requirements:

Many weanlings are able to compensate after a short period of restricted energy supply, during the winter months for example, which should not affect their growth long term. Whilst meeting requirements is key, care should be taken not to excessively exceed the weanling’s energy requirement as this may increase excitability and the risk of the foal developing DOD and other skeletal abnormalities due to periods of rapid growth.

Overfeeding and thus providing the weanling with too much energy will induce rapid growth and puts excessive stress on the joints causing them to grow abnormally. These abnormalities can be seen from feeding as little as a third more energy than the weanling requires, however once the correct energy supply is provided you must then consider other nutrient needs to continue supporting optimum growth.

Protein Requirements for Optimal Growth

Amino acids are the building blocks of protein and are classed as essential amino acids that must be obtained from the horse’s diet, and non-essential amino acids that the horse is able to create internally. Protein is required to form structural molecules such as collagen and can also be found in cell membranes, enzymes, antibodies, and hormones, making them vital for the body to function, grow, and repair.

The only essential amino acid for which a daily requirement has been calculated for horses is Lysine, and we can see from Table 1 that the crude protein (CP) and Lysine requirements increase as the weanling grows. Lysine is also the first limiting amino acid which means even if the horse is receiving more CP in their diet than needed, they can still be deficient in protein if insufficient Lysine is provided. This is particularly key for the weanling as it may hinder their growth and development.

Exceeding protein requirements is unlikely to have any detrimental effect, yet limiting it can result in reduced body weight, height, and cannon bone circumference in weanlings under twelve months old. Like DE, the CP requirements for a six-month-old weanling are greater than those of a 500kg adult horse at maintenance, being 676g compared to 630g per day, respectively.

These requirements highlight the need for quality forage and feed to be provided at this vital growth phase. Supplemental feed should contain at least 16% crude protein with 0.7% Lysine. In one study, 12 weanling foals were given 70%, 100%, or 130% of their energy and protein requirements as indicated by the National Research Council. Even though they were also provided with 100% of their Calcium and Phosphorus requirements, both over and underfeeding of energy and protein negatively affected their growth plate cartilage, which could influence their future development and ability to undertake an active lifestyle.

Essential Vitamins and Minerals for Bone and Muscle Development

From six to twelve months old most of the weanling’s macro mineral, trace element, and vitamin requirements increase between 23% and 33% (Table 1), with the exception of Calcium which stays relatively the same, and Phosphorus which does not change at all. Minerals are vital as they ensure growth and development of skeletal and muscle structures. Calcium and Phosphorus are considered together and are both incredibly important for the weanling as they are used for bone development and muscle function. A deficiency of either or both of these minerals (or an imbalance in the ratio of Calcium to Phosphorus which should be 2:1) can negatively affect bone and cartilage formation.

A high-grain diet may be high in Phosphorus and lead to a negative imbalance and induce a Calcium deficiency, whereas weanlings on a forage-only diet may be deficient in Phosphorus. It has also been shown that a diet deficient in Copper can lead to skeletal problems due to poor collagen quality, osteochondrosis lesions, and weakened cartilage. In order to maintain Copper metabolism, Zinc must be supplied in the appropriate ratio of 1 part Copper to 3.2 parts Zinc, otherwise, it may inhibit absorption.. Manganese is used for the formation of Chondroitin sulphate, which is integral for healthy cartilage, and so must not be overlooked for the vital growth phase of the weanling.

Vitamins must also be considered key to the diet. Fresh forage is high in Vitamin A and deficiencies are rare however cut forage will begin to lose its vitamin content over time. Over supplementation of Vitamin A can have negative effects such as hyperextension of various joints and ataxia (lack of muscle control and coordinated movement), whilst a deficiency will hinder immune and reproductive function. A weanling is only probably prone to a Vitamin D deficiency if they do not have access to fresh forage and are kept inside out of daylight which is not the case for most foals. A Vitamin D deficiency can, however, decrease the quality of skeletal development. Vitamin E is required for immune function and deficiency may result in the degenerative condition Equine Degenerative Myeloencephalopathy (EDM), although this is only likely if the horse does not have access to pasture.

The Role of Forage and Supplements in a Weanling’s Diet

A high forage diet is required for normal gastrointestinal tract function and health as well as to support the natural behaviours of the weanling. Providing a forage-only diet, if good quality, will likely meet the weanling’s energy and protein requirements. However, a preserved forage-only diet is expected to be deficient in all of the necessary vitamins and minerals and supplementation will be required, whether this is in the form of a feed or supplement. Deficiencies in Calcium, Phosphorus, Zinc and/or Copper may also worsen the effects of exceeding the weanling’s energy requirements.

Summary

Growth is not only affected by the diet but also by genetics and the weanling’s environment. Body weight alone is not an ideal indicator of the effect of nutrition on the weanling, whereas analysing wither height and other skeletal developments are likely to be more useful. Body condition scoring has a place to ensure youngsters do not become overweight, however, it should not be used in isolation due to this being a rapid growth phase and short-term fluctuations in growth to be expected.

Good quality forage (hay/haylage and grazing) along with a youngstock feed or the addition of a vitamin and mineral supplement containing quality protein, should be more than adequate to keep your weanling in good condition and set them up for their future careers. Weanlings on spring and summer grazing will need far less supplementary feed for calories than those consuming hay or haylage in the autumn and winter periods, but care must be taken to ensure they are still receiving their vitamins and minerals. Sending off forage and pasture for analysis will allow you to determine what nutrients your weanling will need to be supplemented with. Both under and over feeding can negatively affect bone development and neurological function.

The aim is to maintain a consistent growth pattern and therefore neither exceeding or failing to meet nutritional requirements is what owners should aim to achieve. Weanlings should also be considered as individuals; have their diets tailored to their own needs, and adjustments made when appropriate.

If you would like any advice, please contact our Equine Nutrition Team who would be happy to help you. You can email [email protected] or call our freephone advice line on 0800 585525.