Alison Morris, BSc(Hons), HND and FHEA

Equine Metabolic Syndrome (EMS) is not a disease but a collection of risk factors for endocrinopathic laminitis (laminitis due to an underlying endocrine issue). Ericsson et al. (2021) describe it as similar to the human conditions of metabolic syndrome and type II diabetes. Therefore it can be described as a metabolic type. It describes an insulin resistant phenotype with core symptoms of insulin dysregulation (ID) and increased risk of current or historical laminitis in horses, ponies and donkeys (Geor et al., 2013). Laminitis is a primary clinical consequence and more than 90% of equines with laminitis have developed it as a result of endocrinopathic disease, Morgan et al. (2015) say this is often as a result of EMS. A consensus statement produced in 2019 by the European College Equine Internal Medicine (Durham et al., 2019) states there is little epidemiological data defining the prevalence of EMS but that the condition seems more likely in physically inactive animals. Generally, our equine population is less active than it once was, concluding it is probable this condition may be increasing in the population.

Insulin dysregulation can be described as hyperinsulinemia when excessive or prolonged responses occur to oral or intravenous carbohydrate challenge or tissue level insulin resistance. Obesity has been linked with the condition and EMS affected equines typically exhibit generalised or regional adiposity (Rendel et al., 2018) or a predisposition to weight gain, but obesity is not seen in all cases.

Diagnosis is based upon clinical evaluation, basal insulin concentrations and response to glucose challenge. Clinical presentation can be similar to that of Pituitary Pars Intermedia Dysfunction (PPID) (also called Cushing’s disease) and the two conditions can occur simultaneously. The aim of diagnosis is to manage the increased laminitis risk these animals are at and to allow for evidence-based management strategies to be implemented, that will minimise this risk. Management of afflicted animals is based upon dietary control and if possible increased exercise.

OBESITY AND EMS

Obesity is defined as excessive adiposity that has a negative impact on health and is currently considered to be one of UK’s most serious welfare issues facing equines. Increasing rates of equine obesity are widely reported, with UK rates reported as 31-54% of the overall population (Furtado et al., 2021), rising to approximately 70% in native pony breeds (Rendel et al., 2018). Misinterpreted workload and feeding regimes plus the increase in equines being kept purely as companions are factors linked with increased obesity and its acceptance. Animals may have generalised fat accumulation or regional adiposity. Animals with EMS often have a predisposition to excessive adiposity or are challenging to achieve weight loss in. Fitzgerald et al. (2019) suggest that regional adiposity is a stronger indicator of EMS than generalised adiposity. Adiposity should be evaluated through body weight (BW) determination, fat scoring and cresty neck scores.

MANAGEMENT OF EMS

We need to address the lifestyles of diagnosed horses, with increased physical activity, weight loss (if obese) and dietary management frequently being required. Weight loss in theory is easy to achieve; if the amount of calories being used each day is greater than the calories being ingested then weight loss should occur. Furtado et al. (2021) concluded that UK leisure horse owners were unable to assess the ideal body condition and that they felt unable to identify when their own horse was overweight. They also stated that they found excess condition difficult to differentiate from the shape they thought their horse ‘was meant to be’. Owners felt that weight management was difficult due to complex changes required in the management of their animals and described it as being a ‘battle or war’ and that they perceived it had a negative impact on welfare. Professionals utilising collaborative approaches with owners when attempting to address weight loss in horses were more effective (Furtado et al., 2018).

EXERCISE IN MANAGEMENT

Using exercise to increase the calories being used each day is advantageous for weight loss. Previously laminitic horses should be sound, have lamellar stability and be given veterinary approval to begin an exercise programme. Alongside the weight loss benefits, exercise also improves insulin sensitivity and even low intensity work of 5 minutes trotting per day was seen to normalise some blood parameters in previously laminitic ponies (Menzies-Gow et al., 2014). If horses are able to have increased exercise programmes this can be a beneficial element to their management. To improve short term baseline insulin levels moderate intensity exercise is recommended. Durham et al. (2015) suggest that previously laminitic animals who are now sound and with stable hoof lamellae should undertake low intensity exercise (Heart rate 110-150 bpm) for 30 minutes or more at least three times per week. For non-laminitic horses with ID they suggest moderate intensity exercise (Heart rate 130-170 bpm) for 30 minutes or more at least five times per week.

BODY WEIGHT MANAGEMENT

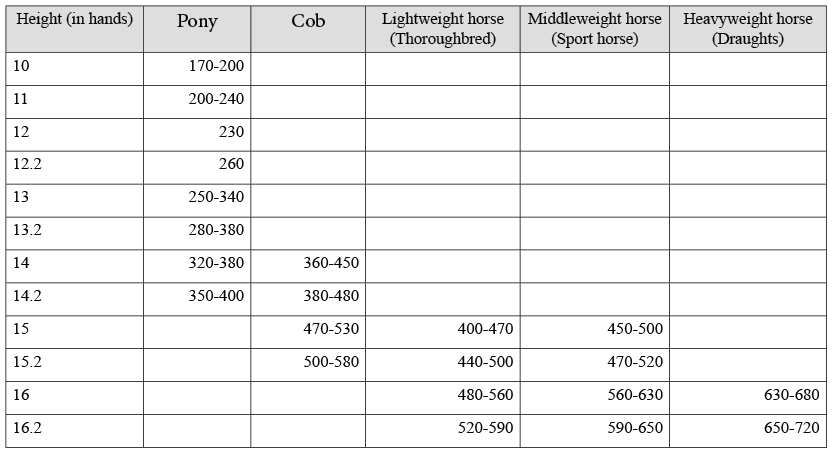

In overweight or obese animals, the aim is weight loss of between 0.55–1% BW/week until an ideal body weight is achieved. However most animals will require continuous body weight management after this. Regular body weight and body condition recording is recommended. Ideal body weights are individual to each animal, however the Blue Cross suggest approximate weights for horses on the basis of their height and type as outlined in table 1. If possible, weighbridges should be used to determine current body weight, however if this is not available an equine weigh tape is also suitable.

Table 1. Approximate horse and pony weight guide (in kg)

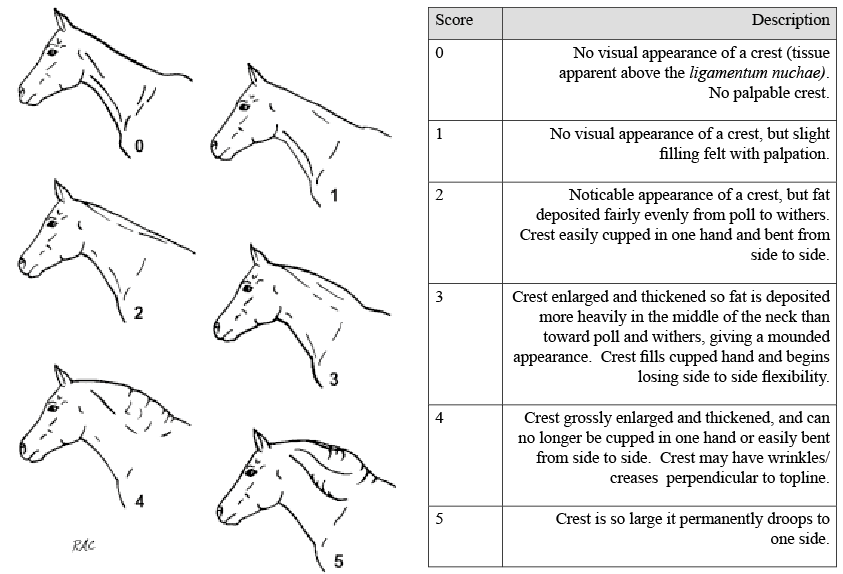

The use of fat scoring or body condition scoring procedures can be extremely useful and while these are subjective, they can be used to assess excess fat and changes in fat level. Cresty neck scores (Figure 1) have been suggested as more predictive than body condition scores of insulin dysregulation in ponies (Fitzgerald et al., 2019). This study concluded that ponies with a cresty neck score of 3 or more were five times more likely to be insulin dysregulated than those with a score below three.

Figure 1. Cresty neck score in horses and ponies Source: (Carter et al., 2008)

Reprinted from The Veterinary Journal, 179/2. Rebecca A. Carter, Raymond J. Geor, W. Burton Staniar, Tania A.Cubitt, Pat A. Harris. Apparent adiposity assessed by standardised scoring systems and morphometric measurements in horses and ponies, 204-210., Copyright (2009), with permission from Elsevier.

As Furtado et al. (2018) determined that owners considered weight loss as a negative experience and something that would compromise the animal’s welfare, a reframing of owner perception may be required. Pickering & Hockenhull (2020) concluded that horse owners tend to consult other people rather than professional organisations and that equine veterinarians are an important source of information. Owners were also found to like practical information on the implementation of welfare improvements.

DIETARY MANAGEMENT

Factors associated with the feeding and nutrition of the horse are often associated with divergence from the animals natural feeding patterns and food types. Horses have evolved as trickle feeders who are reported to graze and browse for between 14–20 hours per day. They ideally require high fibre diets eaten almost continuously, which may be at odds with restricted diets. Domestication and current management practices often involve diets with reduced fibre intake, highly nutritious fibre sources, and inclusion of concentrated feeds, all resulting in altered time budgets and possible weight gain. Providing a lower calorie, more fibrous diet is recommended to encourage weight loss, with such dietary changes being made gradually over a period of ideally 14-21 days to allow the digestive tract time to adapt to new feeds.

All EMS diagnosed equines require dietary management. However all changes must occur with the animals overall welfare at the heart of the diet and the diet should not induce other health issues eg hyperlipidaemia or gastric ulcers. Careful management is required to allow horses to meet their physical and physiological requirements to chew for extended periods.

For obese animals the aim is twofold

- To achieve weight loss and a normal BW and to make dietary changes that reduce the risk of future weight gain

- Reducing the intake of non-structural carbohydrates (NSC’s)

Reducing NSC intake is also required in non-obese EMS equines, to limit the postprandial (after eating) insulin response. Recommendations for both groups therefore include - exclusion of grains from the diet, feeding forage with less than 10% NSC, soaking of forage for 7-16 hours in cool conditions, and exclusion of treats with high NSC (Durham et al., 2019).

Grass turnout is normally linked to high dry matter intakes (DMI) and many pastures have high NSC levels that has been shown to exacerbate hyperinsulinemia in ponies. Durham et al. (2019) suggest that during the first 6-12 weeks of dietary adaptations in ID positive horses, pasture should be fully removed from the diet. Work by Ince et al. (2011) indicated that reducing grazing time is ineffective in ponies as they appear to alter intake to compensate for this. Longland et al. (2011) displayed that grazing muzzles decrease intake and therefore may be a useful tool to allow horses with ID that is under control, to have some grazing. See Managing our horse’s grass intake for further information.

Most horses when given ad-libitum access to forage are seen to eat between 2-2.5% BW DMI per day (NRC, 2007). Starvation style diets are not recommended and can lead to the development of hyperlipidaemia and other health problems while also causing welfare issues. Minimum forage intake of 1.5% BW DMI per day is recommended to reduce dry matter intake. Overweight / obese animals should receive 1.5% BW DMI per day but of a lower energy content forage, ideally over four meals, although this may not be practical for some owners. Straw may be very gradually introduced and included at up to approximately 0.25% BW per day to reduce overall energy intake, intakes higher than this may predispose the horse to equine gastric ulcers (Sykes et al., 2015). Hay may be soaked to reduce NSC content. Hay soaked for 7-16 hours at ambient temperatures saw sugar and fructan levels (water soluble carbohydrates – WSC) decrease between 24-43% (Durham et al., 2019) and was associated with increased body mass losses in comparison to dry hay. Steaming this soaked hay would be ideal to reduce any increases in microbial growth that have likely occurred. If ambient temperatures are increased or water temperature is tepid/warm, then soaking time should be reduced to 1-2 hours (Durham et al., 2019). If animals remain weight loss resistant at these intake levels then intake can be reduced to 1% BW DMI. Animals at this reduced intake should be monitored by a veterinary surgeon to manage the risk of other problems such as colic or gastric ulcers. If animals appear to be weight loss resistant evaluate other potential food sources such as bedding, as Curtis et al. (2011) found that horses undergoing dietary restriction were calculated to eat more than 3kg/day of wood shavings. If digestible energy requirement has been calculated then intake at 64-94% of DE maintenance requirements can be fed (Durham et al., 2019). When intake restrictions are in place attempts should be made to extend eating time as periods of more than four hours without access to forage are linked with increased risk of gastric ulcers (Sykes et al., 2015).

In some cases the veterinary surgeon may recommend the use of pharmacologic aids to assist with the effects of the diet and exercise adaptions in place. When attempting to manage ID, a drug Metformin hydrochloride can be used to manage postprandial blood glucose and insulin levels. Levothyroxine may be prescribed to increase weight loss alongside the dietary and exercise adaptions. These and other options are available and a detailed discussion regarding the use of any medications should occur with the veterinarian responsible for the horse’s care. It is possible for horses to have PPID and EMS concurrently and these horses will likely be treated with Pergolide to minimise the effects the PPID will have on ID (Durham et al., 2019).

A key element of EMS for the horse owner or caregiver is continued monitoring of the animal. Body weight, fat/condition scoring and cresty neck scores should continue even after ideal bodyweight is achieved. Reassessing responses to oral carbohydrate challenge tests to monitor ID should occur in line with veterinary recommendation.

Figure 2. Horse with a cresty neck score of 4 on a scale of 0-5.

SUMMARY

Equine Metabolic Syndrome is a collection of risk factors for endocrinopathic laminitis and can be considered a metabolic type. Core symptoms include ID, and current or historical laminitis. Obesity is linked with the condition and EMS affected equines typically exhibit generalised or regionally adiposity or a predisposition to weight gain. However, obesity is not seen in all cases.

Management of EMS should include exercise, and body weight and dietary management. Exercise in sound animals can assist in reducing body weight and improving insulin sensitivity. Animals should be maintained at an ideal body weight and fat/condition score. Cresty neck scores of below three are ideal. Weight loss should be no more than 1% BW per week and intake levels should be 1.5% BW DM per day for weight loss. In weight loss resistant animals this can decrease to 1% BW DM per day but only under veterinary supervision. Horses should be removed from pasture until ID is under control and BW is considered ideal. Forage should have an NSC level of less than 10% and soaking may be beneficial to achieve this. Inclusion of a suitable vitamin and mineral supplement will ensure adequate levels are provided. Continued monitoring of the horse is required to maintain ID and body mass at suitable levels.

REFERENCES

Blue Cross (Unknown) Fat Horse Slim – A practical guide for managing weight loss in horses. Available at: https://www.bluecross.org.uk/sites/default/files/d8/2020-05/Fat%20horse%20slim.pdf Accessed: (18/02/2020)

Carter, R.A., Geor, R.J., Staniar, W.B., Cubitt, T.A. & Harris, P.A. (2009) Apparent Adiposity Assessed by Standardised Scoring Systems and Morphometric Measurements in Horses and Ponies. The Veterinary Journal. 179(2): 204-210

Curtis, G.C., Barfoot,C.F., Dugdale, A.H.A., Harris, P.A & Argo, C. (2011) Voluntary Ingestion of Wood Shavings by Obese horses Under Dietary Restriction. British Journal of Nutrition, 106(S1): S178 - S182

Durham, A,E., Frank, N., McGowan, C.M., Menzies-Gow, N.J., Roelfsema, E., Vervuert, I., Feige, K. & Fey, K. (2019) ECEIM Consensus Statement on Equine Metabolic Syndrome. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 33: 335-349

Ericsson, A.C., Jonson, P.J., Gieche, L.M., Zobrist, C., Bucy, K., Townsend, K.S., Martin, L.M., & LaCarrubba, A.M. (2021) The Influence of Diet Change and Oral Metformin on Blood Glucose Regulation and the Fecal Microbiota of Healthy Horses. Animals, 11(4): 976.

Fitzgerald, D.M., Anderson, S.T., Sillence, M.N & DeLat, M.A. (2019) The Cresty Neck Score is an Independent predictor of Insulin Dysregulation in ponies. PlosOne. 14(7): e0220203

Furtado, T., Perkins, E., Pinchbeck, G., McGowan, C., Watkins, F & Christley, R. (2021) Exploring Horse Owners’ Understanding of Obese Body Condition and Weight Management in UK leisure horses. Equine Veterinary Journal, 53: 752-762.

Furtado, T., McGowan, C., Perkins, E., Pinchbeck, G., Watkins, F & Christley, R. (2018) Lost in Translation: Examining Communication between Horse-Owners and Professionals about Equine Weight Management. Equine Veterinary Journal, 50(Suppl 52): 11

Geor, R.J., Harris, P.A. & Coenen, M. (2013) Equine Applied and Clinical Nutrition, Health, Welfare and Performance. London : Saunders Elsevier.

Ince, J., Longland, A.C., Newbold, J.C. & Harris, P.A.(2011) Changes in Proportions of Dry Matter Intakes by Ponies with Access to Pasture and Haylage for 3 and 20 hours per day Respectively for six weeks. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 31(5-6): 283

Longland, A.C., Barfoot, C., & Harris, P.A. (2011) The Effect of Wearing a Grazing Muzzle v’s not Wearing a Grazing Muzzle on Pasture Dry Matter intake by Ponies. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 31(5-6): 282-283

Menzies-Gow, N.J., Wray, H., Bailey, S.R., Harris, P.A., & Elliott, J. (2014) The Effect of Exercise on Plasma Concentrations of Inflammatory Markers in Normal and Previously Laminitic Ponies. Equine Veterinary Journal, 46(3): 317-321

Morgan, R., Keen, J. and McGowan, C. (2015) ‘Equine Metabolic Syndrome’. Veterinary Record. August. Pp 173-179.

National Research Council (USA) (2007) Nutrient Requirements for Horses. 6th edn Washington DC: National Academy of Sciences.

Pickering, P., & Hockenhull, J. (2020) Optimising the Efficacy of Equine Welfare Communications: Do Stakeholders Differ in Their Information-Seeking Behaviour and Communication Preferences? Animals, 10(1): 21

Rendel, D., McGregor Argo, C., Bowen, M., Carslake, A., Harris, P., Knowles, E., Menzies-Gow, N., & Morgan, R. (2018) Equine Obesity: Current Perspectives. UK-Vet Equine, 2(5): 1-19

Sykes, B.W., Hewetson, M., Hepburn, R.J., Luthersson, N & Tamzali, Y. (2015) European College of Equine Internal Medicine Consensus Statement – Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome in Adult Horses. Journal Veterinary Internal Medicine, 29: 1288-1299